sohliloquies

cracking general substitution ciphers

3 February 2015As some of you have requested, today we’ll be talking about paper-and-pencil cryptography and how we can use computers to poke it full of holes!

We’ll start with some background on basic (pre-digital) cryptography. Then we’re going to describe the specific cipher we’ll be attacking, along with some standard paper-and-pencil approaches to cracking it. After that, we’ll discuss an algorithmic approach powered by a dictionary file.

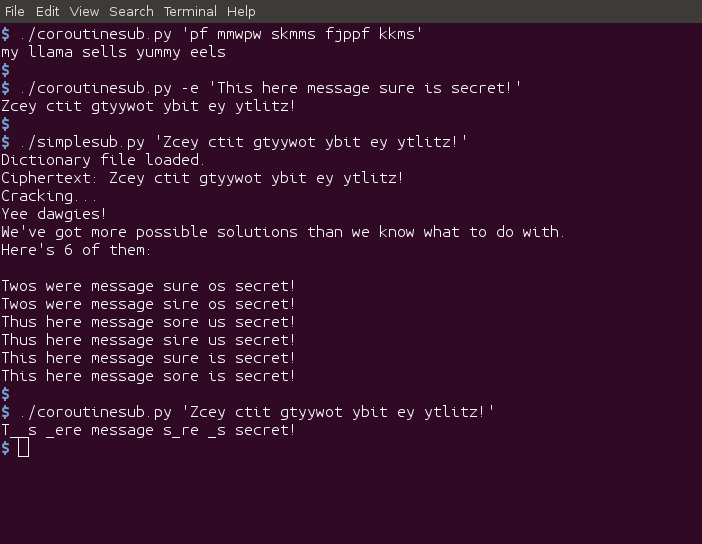

Two Python scripts are provided: A simple one written to be easy to understand, and a fancy one which elegantly implements the main logic using coroutines.

background

A substitution cipher works just how you might think: plaintext is turned into ciphertext by substituting, for each letter, some fixed other letter. A famous special case here is the Caesar cipher, where each letter is replaced by a letter n places after it. The dictator’s preferred value was n=3, like so:

Plaintext: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z

Ciphertext: x y z a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w

Traditionally, uppercase letters are used for both ciphertext and plaintext. However, I’ve always thought this makes it look like the plaintext’s author is in a really bad mood, and so this post’s convention convention is to use all lowercase instead.

Using the traditional Caesar cipher, a message reading (for example) “gaul is subdued” would, when ‘encrypted’, read “dxri fp pryarba”.

Julius used this scheme to encipher secret messages for his generals. More recently, a prominent Mafia boss, Bernardo Provenzano, used a slightly modified version of the Caesar cipher for similar communications. History has no record of how well the cipher worked for Caesar, but Provenzano’s use of it is known to have contributed to his arrest in 2006. Caesar ciphers are weak, and using one is a bad idea.

There are only 25 options for how to shift the alphabet – meaning only 25 possible decryptions for any ciphertext – so it is trivial for an attacker to just try each option and see if any of them work.

The Caesar cipher is too weak to be of any use, but it a nice introduction to substitution ciphers. In a general substitution cipher, each letter is replaced by another letter, but the replacement letters are not necessarily in alphabetical order. For example:

Plaintext: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z

Ciphertext: y a g f t b r i l m o k s u v h e p n w j c q x d z

Some sources say it is unwise to let any letter correspond to itself, as x and z do in this scheme. However, this is a minor issue here, since both are uncommon letters. In fact, what is actually unwise is the use of a substitution cipher at all, as we are about to see :)

Ask yourself: If you intercepted a message that you knew used a general substitution cipher, how would you try to crack it?

The classic attack uses a method called frequency analysis – looking at how often various letters appear and conjecturing that the most common ciphertext letters may correspond to common plaintext letters (e.g. E and T for English text). The cryptanalyst tries out these substitutions, then tries to fill in the blanks by guesswork.

Frequency analysis can be performed on letters; it can also be performed on pairs of letters. This is known as bigram analysis. Certain bigrams, such as for example ‘th’, ‘in’, ‘er’, and ‘nd’, are very common. These pairs of letters will show up in plain English much more often than ones like e.g. ‘wt’ or ‘nz’.

Counting ciphertext bigrams and conjecturing correspondences to common English bigrams can be productive in conjunction with basic frequency analysis. In particular, if a likely translation for one of the letters in a common ciphertext bigram is known from basic frequency analysis, bigram analysis can help with making educated guesses about the full bigram.

These techniques work well for the average hobbyist or luddite working with paper and pencil. However, they are both very slow, prone to errors, and based on guesswork. On top of that, even after applying both of them, filling in the blanks can be very difficult, a bit like trying to finish a half-solved crossword puzzle without any hints. In fact, it’s worse! Since the letters you do ‘know’ are based on guesswork, and since your guesses could be wrong, you might be working on a puzzle with no solution! Surely there must be a better way.

enter the computer

Enter the computer. We have no need these days to solve these puzzles by hand (unless we want to!). We now can leverage algorithmic techniques to solve this problem in a fraction of a second. Here’s the idea:

Frequency analysis works because the mapping between plaintext and ciphertext alphabets is bijective, meaning one-to-one: each ciphertext letter corresponds to exactly one plaintext letter, and vice versa. One letter, and only one. We will not be implementing frequency analysis, at least not directly, but we will be leveraging this one-to-one property.

We assume we know the plaintext’s language, and in a fit of optimism we further assume that we can provide a dictionary file enumerating every word which might appear in the plaintext. In most *nix environments, a good dictionary file is present at /usr/share/dict/words.

The idea is to take advantage of letter repetitions within words. Let’s illustrate it by example. Here’s a ciphertext:

pf mmwpw skmms fjppf kkms

We notice right away that the most common letters are ‘m’, which occurs five times; and ‘p’, which occurs four times. These letters might correspond to E or T. Frequency analysis can be unreliable for such small sample sizes, but let’s try it. If we substitute ‘e’ and ‘t’ for ‘m’ and ‘p’, respectively, and denote everything else with a blank, we get: t_ ee_t_ __ee_ _____ __e_, which is just an absolutely hopeless mess. Do you know any words that start with two Es and have a T in the middle? I don’t. Let’s throw aside these guesses and see what letter repetition can tell us.

The ciphertext’s first word is “pf”. Our /usr/share/dict/words file contains 180 different candidate plaintext words. Examples: ‘as’, ‘in’, ‘my’, ‘ma’, ‘ye’, etc. How is this any better, you might ask? Hang in there.

The second word is “mmwpw”. This is where our word-matching idea starts to shine, because it turns out that our dictionary file has exactly one word with this pattern of letter repetitions. That word is “llama”, so we can conjecture “mmwpw” -> “llama”. This gives us three valuable substitutions.

Of the 180 possibilities for the first word, only 13 of them start with the letter m. So, starting from the start, and trying each possibility for the first letter, 13 of these possibilities will include the conjectured substitution ‘p -> m’. It is only in these cases that we will be able to deduce that the second word is llama. Any other candidate substitution for ‘p’ will fail to find a candidate for this second word.

So, now, for each of these 13 possible first words, we’ve figured out the second word. We now have a bunch of possible partial plaintexts: ms llama ..., mr llama ..., mt llama ..., my llama ..., and so on. An exercise for the reader: decide which, if any, of these guesses sounds funniest. In the meantime, we proceed to the third word.

By inspecting the word’s internal repetitions, we identify six possible decryptions: ‘sells’, ‘shoos’, ‘sills’, ‘tweet’, ‘yummy’, and ‘yuppy’. We now bring in our candidate substitions: Whatever the word is, we expect it to match the pattern, __ll_. We apply this pattern to our candidates and find that only ‘sells’ and ‘sills’ pass the test.

So ‘skmss’ is either ‘sells’ or ‘sills’. ‘k’ hasn’t shown up yet in any of our previous words, so we can’t tell yet which of those is the correct one. Not yet, at least.

We now have 13 * 2 = 26 possible plaintexts (down from 180!) and two words left to go. Not bad!

I’ll spare you the blow-by-blow. These last words have 6 and 7 possibilities, respectively, ignoring substitutions. Once we apply our conjectured substitutions, we can trim those numbers down to the point where we have one decryption:

my llama sells yummy eels

And there you have it.

code

Ok, that’s enough narrative. Let’s talk implementation. I’ve included some Python scripts below which implement the general strategy we used above. The code is internally documented, so I won’t discuss it in detail. A broad overview, though, seems appropriate.

The essential flow is: We generate a dictionary documenting all the words we know to follow any given pattern of letter repetitions. Then, starting from the ciphertext’s first word, we run a depth-first search of the possibility tree. In this tree, each non-leaf node is a plaintext word guess, and every leaf node is either an internally consistent decryption or a dead end. Our search allows us to enumerate these leaf nodes and return to the user those which represent valid candidates.

Here are some GitHub links so you can read the source code. Here is the simple version, and here is the fancy version. I like them both.

The coroutine-based version implements a couple optimizations to improve its runtime and memory footprint. It also only prints out a single guess. Letters which had several possible decrypted values are denoted in the plaintext by an underscore, rather than printing out tons of guesses. There’s no deep reason for this; I just think it looks nicer.

food for thought

-

Frequency analysis never shows up explicitly in our code. However, since it is of course based on letter occurrences in plaintext, it is sort of used indirectly, in a sense, due to our use of a dictionary file. Are there any optimizations or cool features which could come from using frequency analysis in a more explicit way?

-

The biggest limitation of this code is that it only works if every plaintext word is in our dictionary. Uncommon names, acronyms, code names, or randomly inserted gibberish words could all trip up the algorithm. I don’t like this. It would be trivial to make the search consider, in addition to each guess for any given word, the possibility of just skipping that word. This is tricky, though, because then we would suddenly have a lot of leaf nodes which aren’t either dead ends or fully decrypted plaintexts. If we are to consider these, how do we rank them? Perhaps frequency analysis could play a role in scoring these candidates?

-

These days, modern cryptography has entirely supplanted classical cryptography for obvious reasons. However, up until the mid-1800s, the Vigenere cipher was considered to be an excellent (“unbreakable”) cipher. It was, of course, oversold, but the truth is that the Vigenere cipher is not a trivial thing to crack. What would a program designed to attack Vigenere ciphers look like? Could any of the ideas from this post be adapted?

-

Often in practice messages were stripped of all spaces and punctuation and then transmitted in fixed-width blocks. This obviously had the potential to introduce ambiguities, but it also made the cipher less trivial to crack by masking word boundaries. Could this algorithm be adapted to work even in this case? How?

-

Another way to strengthen the cipher while preserving some amount of plaintext readability is to simply include spaces as an entry in the substitution alphabet. It appears that this was rarely done in practice. I am not sure why (maybe due to concerns about trailing spaces?). Our algorithm can be adapted to attack such ciphers simply by iterating over all 27 letters, conjecturing for each letter in turn that it decodes to space, and then making appropriate substitutions and running the above algorithm on the resulting message. This would work, but it increases the algorithm’s (already negligible) running time 27-fold. Is there a better solution?

-

Does this algorithm parallelize well? What are the obstacles? What are the strengths? I have some ideas for how the coroutine version could be modified very slightly to run well in a parallel setting. Perhaps that could be a future blog post…