sohliloquies

2015 iCTF retrospective

15 April 2015After some delays, last Friday saw the 2015 UCSB iCTF come and go, and it was quite the experience. This is (to my knowledge) the first year that Western has joined the competition. We didn’t exactly get first place, but it was great fun and lots of lessons were learned. Now that it’s over and we’ve had a few days to reflect, here are some thoughts on what we did right, what we could’ve done better, and what caught me by surprise.

There were two big surprises for us this year. First, the sheer number of exposed vulnerable services – upwards of 40, I’m pretty sure – and second, the inability to directly attack other teams.

Exploits had to be developed as Python scripts defining an Exploit class implementing a certain, organizer-provided interface. These scripts were to be submitted to the organizers, who would test them and, if the tests were successful, run them on your behalf against all other teams. Scripts were to be single-purpose, focused on retrieving flags; doing anything else was frowned upon. In particular, damaging or backdooring others’ servers was considered foul play.

Considering the number of services exposed (many reused from previous years – with the same holes – guaranteeing that returning teams would have exploits ready to go immediately!!), getting pwned was a guarantee, and this system prevented everyone from having to revert to backups every few minutes. It was in some ways a disappointment, though, since we went into the competition blind but with a number of cool general-purpose CTF scripts at the ready, all of which would have wreaked havoc in a more no-holds-barred format (as previous years had been) but which turned out to be worse than useless here.

Not everyone on our team knew Python well enough to write the scripts required by this system; and so we ended up with several attacks we could execute manually but which none of our Python devs had time to implement. If we’d had more people and a more clearly defined work process, we could have set up some sort of “assembly line” to handle this bottleneck better, with people hunting for bugs and putting them into a queue on a whiteboard (or, dare I say, post-its). This would have raised our productivity considerably.

I think that one of our main strengths was in triaging, both on defense and offense. Our first task, as soon as we got our VM image decrypted, was to see if we had exploits on hand for any of the recycled services. We had a few. As soon as we’d deployed those, we started looking through any service with source code available. Some quick static analysis (ok, ok, grepping) identified unprotected calls to exec() and friends, which yielded more easy exploits – some of which kept paying dividends throughout the whole competition. It turns out that this is a very easy process to automate. Another tactic that paid big returns was looking for default passwords – I was amazed by how many teams didn’t seem to notice these and left bypasses for all their database protections hardcoded into their web scripts!

We maintained a private GitHub repo for sharing code. This started out as a place to put all the utility scripts we thought we’d get to use. As the unusual nature of the competition became clear, this repo quickly morphed into a different beast. Right off the bat I put in some template Python scripts which less seasoned coders could adapt and base automated exploits off of. As soon as any exploit of ours was accepted by the server, we added it to a folder inside the repo so it could be used as a reference. We also kept, separately, a Google doc where things like port numbers and corresponding services were recorded for reference. We also communicated across computer labs and shared code snippets through WWU’s Slack channel. All of these tools proved to be very useful.

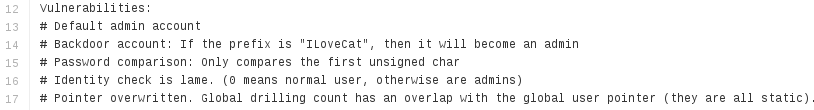

Speaking of Github, roughly halfway through the competition one of our team members discovered this repo and realized that the “services” directory contains full source code for five of the black-box services running on our CTF VM. Incredibly, these scripts were heavily commented, including helpful summaries of their backdoors! Several of these turned out to have been removed in our versions of the services, but many other holes remained – and, remarkably, the docs on Github enumerated many of these as well, sometimes even with sample exploit code!

One nice thing about this particular competition image, with its massive number of vulnerable services, is that now, in the aftermath, we have a ton of toys to play with. I’m looking forward to spending some time breaking as many of these as I can. The prospect of organizing internal mock CTFs using server images derived from this year’s competition image, with different subsets of its services activated, is also an interesting one.

I’m curious to see the degree to which next year’s competition will resemble this year’s. Hopefully most of these lessons will transfer fairly well. After all, now we have a score to beat!