sohliloquies

Resisting Sybil Attacks in Distributed Hash Tables

25 February 2017Tags: theseus

Previously: Theseus: A Robust System for Preserving and Sharing Research

Note: While just about all of the ideas expressed in this blog post live on in my more recent research on this subject, a number of the specifics given in this post are obsolete. In particular, the mathematical analysis is overly simplistic; see also the notes on the hash function discussion below. This post is left up for posterity, but it should not be treated as current or authoritative. An updated version is forthcoming… one of these days.

Introduction

I’m in the process of designing Theseus’s file signature tracking system. A few good options are available here; the one I’m currently leaning towards is a Kademlia-based distributed hash table where the table keys are public keys and table values are lists of signatures by the keyed keys.

The main advantage of this approach is its simplicity. Simple is appealing. Another appealing factor: our use case is very similar to the use case for BitTorrent’s Mainline DHT (MLDHT), which was built to track lists of peers. This similarity means that if we model our approach to a degree on MLDHT then there is a wealth of directly applicable research for us to draw on.

The main disadvantage of this approach is that MLDHT turns out to have some serious security problems at the design level. It inherits these from Kademlia, on which it was based. These problems undermine the DHT’s ability to store data reliably. Similar issues exist for virtually all DHT constructions and seem to be a large part of why DHTs aren’t more widely used. In general these flaws are intractable; however, in the specific case of MLDHT/Kademlia I think they can be overcome.

The specific problem is that Kademlia is susceptible to various forms of the Sybil attack, a class of attack which plagues practically all distributed, decentralized systems. This issue has been known for a long time, and in spite of more than a decade of research on the subject, few if any of the proposed solutions are viable in practice.

Most published defenses fail in a way that falls into at least one of three categories: those that require abandoning decentralization and introducing a central identity-issuing authority; those that rely on some mathematical property available only in certain contexts; and those that simply do not work in the real world. A number of papers suggest establishing identity using social network data (sacrificing anonymity in the process). Most of these papers are interesting only in that they provide examples of all three ways of failing simultaneously.

A few proposals rely on metrics derived from arcane and potentially volatile properties of the network. Some of these are extremely cool and clever, and would probably work in certain settings, but for our purposes they are nonetheless too complex and/or fragile to rely upon.

The 2002 paper which coined the term “Sybil attack” laid out some basic proofs about the ability of these attacks to persist in decentralized peer-to-peer networks even when the protocol includes extreme defensive measures. Most later attempts to introduce identity management through techniques like e.g. computational proof of work end up failing in exactly the ways these proofs predicted. There seem to be essentially no bulletproof techniques for preventing Sybil attacks, and it is perhaps telling that the BitTorrent swarm hasn’t even tried to deploy defenses here.

Trying to get rid of Sybil attacks while maintaining strong guarantees of anonymity and decentralization seems like a lost cause. The story is different, though, for identifying and resisting these attacks. Perhaps it would make sense to just accept the possibility of deploying Sybils on the network and, rather than trying to get rid of them, simply try to design the network in ways that make it easy to respond to them and limit the damage they can cause.

What follows are some ideas for how this could be done in the specific context of a Kademlia-like distributed hash table. My hope is to outline some ways that small additions to the protocol could dramatically increase its resilience without compromising any of its most appealing features.

Apologies in advance for the length of this post. I’m juggling this project with work and my last quarter of undergrad, so I haven’t been able to spare the time to write anything shorter.

Background Reading

If you’re new to distributed hash tables (as I was, prior to this project) and you want to get up-to-speed on this stuff quickly, here are some resources I found useful:

“The Sybil Attack” (PDF) is where the term comes from. This paper lays out the attack in a very general context. Useful as background, though by its nature it focuses on the possibility of establishing Sybils in a network rather than on what those Sybils can do once established. Contains some brief proofs of the Sybil attack’s potency in a variety of circumstances.

“Real-World Sybil Attacks in BitTorrent Mainline DHT (PDF)” goes into specifics. This is a really good paper. It’s based on live research conducted on MLDHT, the most popular distributed hash table associated with BitTorrent. The authors abstract from the attacks they observed to define a taxonomy with three main categories of Sybil attack: horizontal, vertical, and hybrid. I’ll be referencing these terms throughout.

The authors of that second paper have also set up a website for their research. This site has extra info, links to a newer paper studying the network in a more general way, links to slide decks for both papers, links to source code they used, and a whole lot more. Notably, their more recent paper “Measuring Large-Scale Distributed Systems: Case of BitTorrent Mainline DHT (PDF)” contains a methodology for quickly and reliably estimating MLDHT network size, which we will use as a building block later in this post.

“A survey of DHT security techniques” lives up to its name, providing a well-written and dizzyingly thorough overview of attacks and countermeasures in DHTs. This is a long read relative to the other papers linked, but it’s jam-packed with valuable information from start to finish. In particular, it does an outstanding job of identifying flaws in most proposed attack mitigations. The authors’ conclusions are not particularly optimistic.

One thing this paper does a good job of highlighting is that Sybil attacks are not the only attacks on DHTs. Attacks on DHTs’ routing tables are also capable of undermining system reliability. In discussing the applicability of these attacks to Kademlia, they write:

We believe that the main reason for [Kademlia’s widespread adoption] is Kademlia’s combined properties of performance and relative security. For one, it is difficult to affect the routing tables of a Kademlia node, as each node tends to keep only highly available peers in its routing table. This increases the required costs for an attacker to convince honest nodes to link to the compromised nodes. Similarly, Kademlia uses iterative routing, exploring multiple nodes at each step, making routing less dependent on specific nodes and thus less vulnerable to attacks. However, Kademlia is still vulnerable to Sybil and Eclipse attacks as nodes can generate their own identifiers.

This assessment, which seems to be backed by the literature, makes me optimistic for the potential of the techniques discussed in this post to address Kademlia’s main weaknesses.

Wikipedia’s article on Mainline DHT is short but sweet and serves as another nice summary of the protocol. Readers wanting even more detail might be interested in the official DHT BEP (“BitTorrent Enhancement Proposal”), the Wikipedia article for Kademlia (which Mainline DHT is based on), or the original publication describing Kademlia (PDF). That last link includes sketches of proofs of proper function which could help the particularly dedicated reader understand why Kademlia is such an appealing choice for the BitTorrent swarm.

The important things to understand about Kademlia and Mainline DHT for our purposes are:

-

Users are uniquely identified by their 160-bit “user ID” values. The specification mandates that users choose these IDs randomly, but in fact users can set their User ID to whatever they want. This is part of what makes Sybil attacks so straightforward and potent in Kademlia.

-

Hash table keys are points in the same 160-bit space as user IDs. These should also be randomly generated, and in practice they typically come from cryptographic hashes of what it is we’re trying to look up info related to.

-

Users maintain routing tables which are maintained in a way disproportionately favoring nodes whose IDs are close to the user’s own ID by the “XOR metric” (which is exactly what it sounds like).

-

A “vertical attack” essentially consists of an attacker creating Sybil nodes with user ID values extremely close to a table key that they want to interfere with, and trying to get these nodes into as many routing tables as possible. In so doing, the attacker crowds out other nearby nodes and ends up becoming the main – and possibly sole – authority for a given table key. Kademlia and Mainline DHT allow nodes to assign themselves arbitrary IDs, which makes this attack very easy.

-

Needless to say, the consequences of this are severe. Attackers can modify or even refuse to store the data associated with a given key, undermining the reliability of the system without honest nodes even necessarily being able to tell that anything is amiss.

-

Some papers make a distinction between establishing the proximate nodes, which they term a Sybil attack, and using them to serve dishonest results, which they consider a distinct “storage attack.”

-

-

A “horizontal attack” consists of generating Sybils that are as widely distributed throughout the network’s identifier space as possible. An attacker carrying out a horizontal attack is able to gather a significant amount of information about the traffic passing through the network, such as which keys are being frequently searched for.

-

The attacker also gains significant leverage within the system’s control layer and can use this to many ends, such as undermining system reliability or bootstrapping a vertical attack. This process of using a successful horizontal attack to quickly launch a vertical attack (or many vertical attacks) constitutes a “hybrid attack”.

-

Real-World Sybil Attacks in BitTorrent Mainline DHT reports observing (assumed) Sybil nodes engaged in horizontal attacks responding to

FIND_NODEqueries for randomly generated keys as if they had the values for said keys stored locally (but of course ignoring subsequentGET_PEERSrequests).

-

-

An interesting part of the original Kademlia specification which gets surprisingly little mention elsewhere: “For caching purposes, once a lookup succeeds, the requesting node stores the

<key, value>pair at the closest node it observed to the key that did not return the value … To avoid “over-caching, we make the expiration time of a<key, value>pair in any node’s database exponentially inversely proportional to the number of nodes between the current node and the node whose ID is closest to the key ID.” (page 7) This is a good idea, and we will discuss the possibility of leveraging it for defensive purposes.

The Ideas

Securing User ID Selection

The design decision to allow users to pick any IDs they want is a large part of why vertical attacks on MLDHT are so easy. You’re asked and pretty-pleased to choose a random ID, and honest nodes do, but there’s nothing stopping a dishonest node from ignoring that request completely. There isn’t anything keeping untrustworthy nodes honest. But there could be.

The idea here is to calculate user IDs using a cryptographic hash function, and to keep nodes honest by having them share not just their ID but also the input used to generate it. This instantly makes vertical attacks significantly more expensive to carry out, since it turns the problem of finding valid IDs for an attack into the problem of finding inputs whose hashes have a specific prefix. This is well-known to be difficult, and in fact many computational proof-of-work systems, including blockchain technology, derive their security from this problem’s difficulty. We can make the problem even harder by using a deliberately slow hash function. I’ll discuss this in more detail below.

The addition of cryptographic hashes makes vertical Sybil attacks much more expensive while keeping extra cost negligible for honest nodes. However, an adversary with significant computational resources and time to kill could always kick back, set their private compute cluster or armada of AWS boxes or whatever onto the task of brute-forcing the input space for useful IDs, and wait. It might take them a very long time to find enough IDs for a successful attack, but once they’ve crossed that threshold, they can (in a naive scheme) permanently sabotage the network’s ability to store signatures by any targeted key.

As such, what we have so far is still unacceptable. But we’re not done yet. The next idea is to define a format for the hash inputs which leaves every ID with its own baked-in expiration date. More specifically: specify that the hash input must start with, say, the current UNIX time at time of generation, as an integer. Follow that with a large random string to ward off collisions. Since we’re requiring everyone to distribute not just ID hashes but hash preimages as well, peers will be able to extract this timestamp from the preimage, compare it against their own current system time, and accept the node into their routing tables if and only if the difference in times falls below a certain threshold. So for instance we could decide only to deal with nodes whose IDs are stamped with a time from (say) the last 36 hours, or the last 90 minutes, etc. Naturally, timestamps falling in the future would be rejected categorically.

Now, of course, nothing is forcing attackers to use the current time in their brute-force searches. You could absolutely decide to pick some moment a year from now, spend the next year brute-forcing a huge number of IDs for that time, and then deploy them onto the network when their day finally comes. Nothing’s stopping you from doing that. But then they’ll expire, and you’ll be left just where you were before. Your attack essentially comes with an expiration date unless you keep putting resources into renewing it. The effect is to trade off a small increase in apparent user churn for a significant increase in the computational resources required to launch an effective vertical Sybil attack.

The nature of this increase is worth mentioning: while the previous suggestion only increased the entry cost of launching a Sybil attack, this one transforms that one-time cost into a continuous one. Essentially, it introduces an upkeep cost for maintaining the attack, since you have to generate not just one set of malicious IDs but one set per time window you want the attack to be active during.

Another advantage to using a slow-by-design hash function with a timestamp available is that we can use the timestamp to automatically scale the hash function’s work factor in pace with Moore’s law.

One question we still haven’t addressed, though, is: how long should the random bytestring appended to system time be? This is where we reach another idea – artificially reducing the ID space while maintaining even ID distribution among honest users. Controlling the length of this bytestring essentially allows us to control the number of distinct valid IDs. The actual set of valid IDs will change slightly every second, but the size of the set will stay constant, and (perhaps surprisingly) there turn out to be real advantages to considering that size carefully.

The naive approach would be to specify length 160. This trivially guarantees that hash inputs will have at least as much entropy as the outputs appear to. As a result, if the hash function’s theoretical properties hold, then an input corresponding to practically any user ID could eventually be found. But is this a good thing?

Remember, honest users have no reason to want to favor some specific IDs over others, but malicious users executing a vertical Sybil attack have a very strong reason for wanting exactly that. Why do they want to be able to pick specific IDs? Because that’s how they put themselves closer to their target than any honest peers are likely to be. Their influence derives from making this gap between them and the nearest honest peers as wide as possible, and so the peer network clearly benefits from making it as hard as possible for them to widen said gap. We can do this by choosing a length shorter than 160 for the random string. The precise length chosen determines the number of possible IDs in the system, and as a result it also determines, in a well-defined mathematical way, how much better an attacker can do than choosing an ID completely at random.

The analysis is simple but math-heavy and so I’m saving it for the analysis section below. It addresses with all the above considerations and derives certain suggestions for time window size and random bytestring length. Spoiler alert: The values I end up suggesting are 18 hours (≈ 2^16 seconds) for the time window and 6 bytes (= 48 bits) for the random string. The reasoning behind these values is laid out in full down there.

These measures, taken together, make vertical attacks tremendously more difficult to deploy or sustain. The ideas involved are simple enough that I’m sure I’m not the first to come up with them. If anyone could point me in the direction of other prior work in this vein, I’d appreciate it.

That just about covers my thoughts concerning User IDs. There’s one other major topic left to discuss here, and it’s a big one.

Identifying and Mitigating In-Progress Vertical Sybil Attacks

In Wang and Kangasharju’s Measuring Large-Scale Distributed Systems: Case of BitTorrent Mainline DHT (linked above), a methodology is given for quickly and accurately estimating the size of a MLDHT-like network. Knowing the approximate size of the network is very useful. It allows us, for instance, to use simple and well-studied probability distributions to straightforwardly model the number of nodes we expect to find at any given distance from an arbitrary key.

That’s more than a party trick. Once we know what to expect as far as node density, we can check whether reality matches that expectation. This sort of technique might be dicey to apply in a network like MLDHT, which lacks strong guarantees of random ID generation by honest nodes. In a situation like the one proposed herein, though, where IDs are generated by verifiable hashes, we can make strong assumptions about the statistical behavior of a large number of honest nodes.

As a result, if we ever notice that the number of nodes found differs from the number expected by (say) at least two standard deviations, then we can be fairly confident that either 1) we’re wildly mis-estimating the size of the network, or 2) something fishy is afoot.

If the number found is significantly less than the number expected, there’s not much we can do. This is probably indicative of a very widespread horizontal Sybil attack which has cut these nodes out of its routing tables, leaving them impossible to locate as long as the only nodes you query are Sybil nodes or honest nodes who lack knowledge of the isolated set. The most we can really do in this situation is raise a red flag and throw up our hands. It’s worth noting that this attack fails if we can even find just one honest node who knows at least one of the blacklisted hosts. As such, the larger the network gets, the more likely these attacks are to fail. It seems to me, though, that we might never be able to fully rule them out.

(One interesting thought which I haven’t yet fully explored yet is to try and raise the cost of executing such an attack even further by having honest peers with spare system resources engage in a sort of inverted Sybil attack where they operate multiple fully honest nodes in the system, thus helping to increase the ratio of honest nodes to dishonest nodes. While it might be preferable to keep these co-hosted nodes independent, they could potentially share things like routing info or cached key values, which would result in externally non-obvious [& therefore harder-to-undermine] flows of information in the network. This strategy might also increase system stability and reliability while the network has a small number of users. OTOH, it might make churn take a greater toll on the network.)

Back on topic: vertical Sybil attacks involve clustering a large number of nodes in a very small area. As a result, these nodes are unlikely to be included in a random sampling of the network, and sampling multiple areas (as the cited methodology prescribes) reduces this probability even further. So the model we end up with is essentially a model of the distribution of nodes not actively engaged in vertical Sybil attacks. And so, if the number of nodes found around a certain key is significantly higher than this model predicts, there is only one conclusion we can draw: a vertical Sybil attack is in fact taking place on this key, and countermeasures must be taken.

But what countermeasures? Unfortunately, if you’re trying to look up a key, there’s not much you can do here except spread your queries as widely as possible and cross your fingers. But if you’re storing a value, there’s a mechanism you can leverage to your advantage: the pre-existing provisions for caching quoted at the end of the “Background Reading” section.

These provide a simple system by which high-demand keys automatically find their way into a larger number of nodes’ caches, with demand and distance-determined timeouts working as opposing forces to get the system to naturally converge to a sort of equilibrium. In times of high demand, the key gets shared with more and more nearby nodes, until eventually it reaches nodes whose caching timeouts complete faster than key-storage messages are coming in, and the key ends up getting repeatedly refreshed into those nodes rather than getting spread any further.

In the vanilla Kademlia system, XOR distance from a key is the only factor influencing its timeout. But what if there were other factors? What if, for instance, nodes recognized, and afforded a significantly more forgiving timeout to, keys that were under active Sybil attack?

My suggestion here is very simple: add an optional flag to the key storage message type (what Kademlia calls “STORE”, and MLDHT calls “announce_peer”). The presence of this flag, perhaps keyed as “sybil”, would announce that the sender of the STORE message believes the key to be stored is under active Sybil attack.

What the recipient of the message does with this information is of course technically up to them, but one reasonable response would be to verify the claim through independently carrying out the same analysis described above and, if the claim is confirmed, storing the key with a significantly increased timeout period. Sending these requests to nodes outside the suspected radius of the Sybil attack would allow most querying users to resolve their queries before they even reach the untrustworthy, highly concentrated Sybil nodes, effectively bypassing the attack.

This solution hits a bit of a bump when hybrid attacks come into play, since the horizontal nodes could route all requests directly into the highly concentrated, Sybil-ized zone, bypassing the intermediate caching nodes. This is a serious concern, but it could perhaps be mitigated in the client by implementing some sort of threshold for how close you actually want to get to the key value. Since our statistical analysis allows us to conjecture with reasonable confidence as to how far the vertical Sybil attack extends, clients could use this information to make sure to query a certain number of clients from outside this threshold as well as querying the closest IDs from inside it. That could significantly increase our chances of finding an honest node.

I’m expecting that this scheme would be particularly effective in Theseus. Here’s why. As described in my previous blog post on this project, part of the plan is for users to import trusted public keys and seed torrents signed by those keys. The purpose of this DHT is to track those signatures. The DHT gives key owners a simple way of communicating their signatures to the swarm, and it gives seeders a simple way of retrieving these signatures, without the two groups ever needing to directly communicate or even be online at the same. Once a seeder has retrieved all the signatures available from a certain public key, though, they can periodically re-publish this data to the DHT as part of their support of the owner of that public key.

This 1) helps ensure that all of a user’s signatures are tracked, because these seedbox nodes would very quickly build up authoritative lists of publicly known signatures, and 2) ensures that store requests would be taking place frequently enough to assume with reasonable confidence that vertical Sybil attacks would be detected and responded to relatively quickly.

Obviously this idea needs review and testing, but I’m very optimistic about its potential.

The Math

We’ve covered a lot of ground so far, and there are a lot of things I said I’d follow up on here. Let’s start at the start.

Fundamentals

If you’ve got 160-bit IDs, the number of possible IDs is of course \(2^{160}\). Similarly, the number of IDs starting with an n-bit prefix is \(2^{160-n}\).

The XOR metric used to measure distance works by computing bitwise XOR on two inputs and taking the numeric result. If two IDs share an exactly \(n\)-bit prefix, then the first \(n\) bits of their XOR will be 0, and the \(n+1\)th bit will be 1.

If you pick two IDs at random, you can model the expected number of prefix bits shared between them by considering instead the equivalent question of where the first non-matching bit will appear, then applying a geometric distribution with \(p=0.5\). This gives us \(\Pr(\text{prefix length = n}) = 0.5^{n+1}\).

We now have the preliminaries required to model the expected number of nodes whose IDs have any given length-n prefix as a function of swarm size. Following the convention of Real-World Sybil Attacks in BitTorrent Mainline DHT, we’ll denote swarm size by \(N\). The expected number of nodes whose IDs have a given n-bit prefix is equal to the swarm size times the probability of any given node having the prefix, i.e. \(N\frac{2^{160-n}}{2^{160}}\), which simplifies to \(\frac{N}{2^n}\).

(Note: This estimate does not include Sybil nodes engaged in vertical attacks, but it does include sleeper Sybil nodes engaged in slow-burn horizontal attacks, since the latter group is evenly distributed throughout the swarm and in fact behaves functionally identical to honest nodes for most of their lifespan. This is not really a problem, since this methodology is only concerned with detecting vertical attacks, but it is worth noting.)

ID Entropy

Follow-up: While this idea may have some value, it does not feature in my more recent thinking on this subject. The basic motivation here is to place a hard bound on the worst-case scenario for an attack. In some cases this would certainly be a nice property; however, it is not necessary if a worst-case attack is prohibitively expensive in the first place. Also, vertical Sybil attacks produce statistically significant signatures which (to make a long story short) can be detected and routed around. This is not trivial but it is possible, and it is more reliable if you abandon trying to limit the worst-case attack profile and instead opt to let attackers distinguish themselves as much as they care to.

I went over this in a fair bit of detail earlier, so I’ll try and keep this simple. The idea is to generate IDs using a cryptographic hash of an input which follows a very specific format: first, 32 bits encoding seconds since UNIX epoch (UTC) as an unsigned integer. Note that this breaks from tradition: typically, the integer is signed, to allow for representations of times prior to epoch. We have no need for that, so we’ll use unsigned (which also allows us to sidestep the “Year 2038 problem”). Then, a number of (ostensibly) random bits. The precise number allows us to control the number of possible IDs, which in turn allows us to control (at least with overwhelming probability) how much closer Sybil attackers can get to a given ID than any honest nodes can be expected to be.

Lessening this margin potentially forces the attacker to deploy a greater number of Sybils relative to the level of influence desired over a key. Increasing the number of Sybils required makes it easier to use statistical techniques to identify the Sybil attack, thus also making the attack easier to thwart.

I say “potentially” because the degree to which this is the case depends somewhat on the total number of nodes in the network. Essentially, the more honest nodes the network has, the more resilient it becomes. The benefits of reducing ID entropy would be felt in large networks significantly more than small ones – but hey, it’s good to plan ahead :)

How much entropy do we want? Enough that honest users can expect never to see ID collisions, but not much more. That’s a somewhat amorphous definition, but not so much so as it might sound. My inclination is to design around BitTorrent, since anything that would work for that system’s # of users would definitely be enough for this.

The size of the BitTorrent network varies with time of day, and is estimated to range from 15 million during the off hours to 27 million at peak. It’s tempting to use the base-2 logarithm of 27 million (≈ 24.7), but such an approach ignores the birthday problem. Adjusting for this, we find that the actual number of bits required is closer to 48. Using 48 bits means that you can choose at least 20 million keys before having a 50% chance of seeing at least one collision, and 28 million before having a 75% chance of same, so actually it’s a little small for BitTorrent, but for our purposes it’s fine.

My inclination, then, is to set the length of the bitstring to 48. This puts a nice, comfortable, hard lower limit on the entropy of the full input.

BitTorrent is estimated to see about a quarter billion unique users per month. 64 bits of entropy would be enough to uniquely identify twice that number of users with less than a 1% chance of any ID collisions at all. So 64 bits seems like a reasonable upper limit. \(64 - 48 = 16\), and \(2^{16} \text{seconds} \approx 18 \text{ hours}\), which is just too aesthetically appealing a set of figures to ignore. So let’s define the time window at \(2^{16}\) seconds.

Incidentally, while studies of peer churn and session lengths are hard to find, those I could find suggest that the significant majority of peer sessions last less than 18 hours. The time windowing modification naturally only changes the behavior of sessions lasting \(\gtrsim 18 \text{ hours}\), and as such would change the perceived behavior of only a small number of peers.

Vertical Sybil Attacks

TODO: add follow-up summarizing more recent research

The expected size of the required prefix for IDs in a vertical Sybil attack is a function of swarm size. The prefix length should be just barely larger than that of the prefix shared by any honest node with the target ID. We can estimate this length using the statistical model described above.

The expected number of nodes with a given length-n prefix is, again, \(\frac{N}{2^n}\). We’re interested in finding \(n\) such that \(\frac{N}{2^{n-1}} \geq 1\) but \(\frac{N}{2^n} \leq 1\). Since \(\frac{N}{2^n}\) is monotonic decreasing, we can find this by solving \(\frac{N}{2^n} = 1\) for \(n\), ending up with \(\log_2 N\), and then finding the closest appropriate integer value. The end result is \(n = \lfloor 1 + \log_2 N \rfloor\).

This \(n\) is the shortest prefix length required for these Sybil IDs. The odds of finding an ID with exactly n prefix bits is known, but what we’re actually interested in is the odds of finding IDs with at least \(n\) prefix bits:

This gives us the probability of any given input giving us a usable ID. The expected number of trials required to hit such an ID is, naturally, the reciprocal of this value. Multiplying that reciprocal by the number of IDs required gives us the expected number of trials required overall.

The number of IDs required depends somewhat on implementation specifics and on the demand for the given key. High-demand keys are cached more aggressively and thus require more IDs to attack. We’ll start with considering the case of low-demand keys. For these, the number of IDs required depends specifically on the bucket size used by the system (usually denoted by k). MLDHT uses \(k=8\). Larger bucket sizes increase resistance to vertical Sybil attacks by a linear factor.

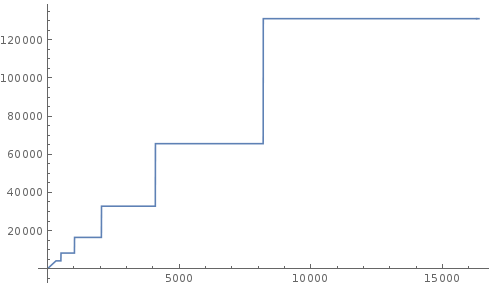

Using the example of \(k=8\), we’d end up with the number of trials required being \(8/0.5^{\lfloor\log_2(N)+1\rfloor}\). Here’s a plot of that function. It looks kinda cool.

|

| Horizontal axis: Number of nodes in network Vertical axis: Number of trials required to find enough IDs for vertical Sybil attack |

It’s clear to see that as the number of peers increases (and thus the density of benign user IDs also increases), the number of trials required increases as well. The function is tightly bounded below by kN. I’m inclined to think that k=8 is a little conservative for our purposes, and that a larger value like say k=16 might be a better choice.

In any case: this gives the difficulty of launching a vertical Sybil attack. Once the attack is launched, the network should detect it through the methodology described above and start to compensate.

The method of compensation suggested above operates by asking intermediate nodes to cache the key longer than they otherwise would. This causes the key to spread in roughly the same way it spreads when under high demand, but without increasing request volume. When this happens, the Sybil nodes start getting essentially cut out from the system, because users start being able to resolve their requests without even having to traverse the network far enough to reach the Sybil nodes. The Sybil attack thus loses its potency unless the attacker takes extreme measures to re-strengthen it.

These measures could take one of two forms: either increasing the scope of the Sybil attack, trying to dominate not only the set of nodes with length-n shared prefixes but also length-(n-1) and length-(n-2) and so on forth; or pivoting to a hybrid attack.

The hybrid attack is somewhat effective, but as noted above, its horizontal component only works well if it manages to completely exclude honest nodes, which would require a tremendous amount of work. And if nodes implemented the filtering system tentatively suggested near the end of the attack mitigation section above, they would likely be able to avoid this threat as well.

The other possibility – increasing Sybil attack scope – is less worrying, at least to me, because for every extra bit of prefix discarded, the amount of work required to maintain the attack’s potency doubles. As such, as scope increases linearly, work increases quadratically. For a well-chosen hash function, this quickly becomes unsustainable.

Speaking of hash functions…

Choosing a Cryptographic Hash Function

Follow-up: While I still really like the idea of scaling the work factor with time, there are other factors to consider. My current preference is to use a modern memory-hard hash function like Argon2, and/or a function that is cheaper to verify than compute, e.g. Equihash. These do a better job of keeping specialized hardware from outperforming consumer hardware. However, their tuning parameters are somewhat less granular, so the question of whether this scaling strategy is viable becomes somewhat more difficult.

The choice of ID-generating hash function is very important and has many implications. I briefly mentioned that I like the idea of using a deliberately slow function here. My inclination here is to use PBKDF2 backed by bcrypt. These are two well-studied and robust algorithms which complement each other nicely. There is also a Python library offering bindings to OpenSSH’s implementation of the bcrypt + PBKDF2 combination, which is convenient since Theseus will almost certainly end up being written in Python.

Quick terminology note: yes, strictly speaking PBKDF2 is a key derivation function, which is related to but distinct from a hash function. Yes, I’m using slightly incorrect terminology by calling it a cryptographic hash function. No, I don’t care.

The nice thing about PBKDF2 (or vanilla bcrypt, for that matter) is that it has a configurable number of rounds (also known as a cost factor). This lets us make brute-force searches arbitrarily hard, and also future-proofs the algorithm against increasing compute power.

Since Moore’s law hasn’t fallen off yet, my inclination is to follow its lead and specify that the cost factor should double every two years, in an attempt to keep hash speed roughly constant across time. We can accomplish this cleanly behind-the-scenes by making the number of PBKDF2 rounds used to hash a given identifier a function of its timestamp.

Specifically, for some constant factor c defining “how hard” we want hash computation to be overall, let the number of rounds be:

ceil(c * 2**(time/(60*60*24*365.25*2)))

= ceil(c * 2**(time/63,115,200))

where that unwieldy number in the exponent is of course the number of seconds in the average year. The question remains of what to set c to. This is something of an arbitrary choice, so I’m arbitrarily choosing to set c = 0.000004. This currently yields 51 rounds, and bcrypt.kdf(b'spam', b'eggs', 20, 51) completes in about 1.2 seconds on my not-quite-up-to-date desktop.

If that sounds a bit slow, remember that hash values, once computed, can be cached, which does nothing to speed up brute-force searches but helps users tremendously, allowing their clients to only compute a hash once per peer. If you’re still concerned, bear in mind that we don’t strictly speaking need to validate everyone’s ID hash – on slow hardware that finds bcrypt taxing, we could default to evaluating (say) 20% of hashes, or some other percentage determined by system speed, and start increasing the percentage if and only if we start noticing dishonest peers.

My main concern at this point is keeping the hashing from being prohibitively expensive for people running on older hardware. That’s the motivating factor behind not picking a higher value for \(c\). I’m certainly open to discussion on this point, though, if it strikes anyone as being lower (or higher) than it should be.

Summary

That was a fair bit of material, and I wouldn’t blame you for skipping over parts of it. For the sake of summary, and to make sure I’m being clear about what my main points are, here’s a very brief and high-level overview of the key ideas in what we just discussed, as I see them. If anything here leaves you wanting more detail…. scroll back up, or leave a comment below.

What I’m describing are three measures to defend against Sybil attacks on a Kademlia-style distributed hash table. Each individual idea might be effective on its own, but together I believe they reinforce each other, creating a whole that is perhaps greater than the sum of its parts. The three ideas are:

- Making it as difficult as possible for attackers to obtain the user IDs necessary to launch a vertical Sybil attack in the first place. This…

- Raises the cost of the attack significantly

- Introduces an upkeep cost to the attack

- Potentially forces the attacker to deploy more Sybil nodes

- Using statistical and probabilistic techniques to model the network, detect when attacks are taking place, and respond to them in ways that render them ineffective

- Having honest peers with spare system resources operate multiple nodes in the network, thus raising the total number of nodes and complicating those types of Sybil attacks which rely on achieving a certain ratio of Sybil nodes to total nodes for their success.

Future Work

The measures outlined here are designed to increase the cost and decrease the effectiveness of vertical Sybil attacks, which if not prevented present a fundamental threat to the reliability of a distributed hash table. I believe that through resistance and detection we can make these attacks practically impossible. These methods need to be tested; if they work, they would together represent something that I’m not aware of any precedent for.

These measures do little, though, to ward off horizontal attacks. A horizontal attack is costlier to carry out than in other DHT implementations, but the cost is not prohibitive. Measuring Large-Scale Distributed Systems: Case of BitTorrent Mainline DHT suggests a way of detecting such attacks which might be a useful basis for future work in this vein. However, it’s hard to say how much can really be done. I’m currently very much taken by the idea of honest peers with spare resources operating multiple honest nodes rather than limiting themselves to just one, in order to increase the swarm size and thus raise its resilience against these attacks somewhat.

A Survey of DHT Security Techniques mentions that Sybil attacks and “eclipse attacks” (which in the terminology used here are somewhat rolled up with what we call vertical Sybil attacks) are the main threats to Kademlia-based designs, and that Kademlia is relatively resistant to other attacks by default. If the techniques suggested in this post bear fruit, it might be worth re-evaluating this claim in the light of that success.

Aside from the measures discussed herein, the biggest thing required to ensure a peer swarm’s security is for it to have a large number of honest users. The more adoption the system sees, the harder it is for attackers to reach a critical mass of malicious nodes. One of the best security measures possible, then, is to get the application into as many people’s hands as possible, and to make sure that as many of them as possible have reason to keep using it.

That is where I see most of the future work in Theseus being. I firmly believe that this can surpass every modern tool for conducting research, and putting in the work to realize that potential is a major priority. Anyone interested in joining in: you know how to reach me.