sohliloquies

Book Notes

12 September 2017Tags: book-notes

Post-graduation, I’ve been finding it easier to carve out free time. Some of this I’ve spent on Theseus and other projects. More of it I’ve spent reading. It’s important for technical people to retain some analog hobbies.

These are notes on some books I’ve read lately. Not everything – just the stuff I’ve liked.

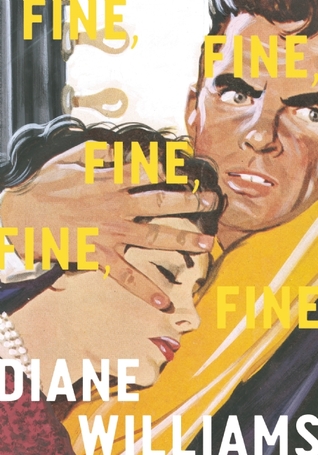

This book’s stories are as striking as its cover. It’s hard to summarize but easy to recommend. Broadly speaking, Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine’s subject is life, sliced thin: Snapshots of specific moments, rarely dramatic but always emotionally fraught. The stories are all really short (three pages or less), and they’re put together with economy, wit, and endless inventiveness.

It’s a funny thing about life how small details can feel so big. So much of the texture of life comes from little things that stick with us even though (or maybe because?) they might not have even been noticed by anyone else. These are the details that we still remember, against all odds, years later. Trying to describe these moments is a sure way to sound silly, or obsessive, or totally out of it – yet Diane Williams manages to craft compelling narratives from exactly these.

She presents these parades of details, their significance to the various narrators somehow conveying the essence of these people’s whole lives. The portraits thus created are uncannily vivid, the more so for their terseness. It’s exciting to see an author do so much with so little.

Occasionally one hits a story so spare and inscrutable as to defy easy comprehension. That’s to be expected. These are little mysteries, all the more fun for their obscurity. And each story that clicks feels like a little secret treasure.

I’ve also got Williams’ Vicky Swanky is a Beauty sitting on my to-read shelf, and after this I’m really looking forward to it.

Highlights: The Romantic Life, Living Deluxe, How Blown Up, There Is Always a Hesitation Before Turning In a Finished Job, Lamb Chops, Cod, Girl With a Pencil, A Little Bottle of Tears

This is the first of DeLillo’s novels that I’ve read. I loved it. Having read so many authors who were admirers of his, it’s kind of surreal recognizing now which of their themes and techniques were borrowed, which of their literary flourishes came from this source. I’m not sure why it took me so long to read this guy. The degree of DeLillo’s influence on his successors (e.g. most obviously Wallace) is immediately recognizable, as is the reason for it.

White Noise itself is so clever and nuanced that it’s a bit of a struggle to resist spending the rest of this post just analyzing it. I won’t put you through that. Instead, here are some things about it that really struck me.

The writing of the main character’s family life is inspired. I found myself recognizing their “modern” tics to a startling degree (especially considering the book was published well before my time). Some of the characters’ particular flaws and dynamics are scarily true-to-life. I wonder if they came off as exaggerated at the time.

The topic of media saturation is, by now, done to death several times over. Remarkably, White Noise, which predates a whole lot of the stuff on this topic, has also managed to stay fresher than most of it. It’s an absolute joy to read.

A perpetual struggle for later authors trying to mine this vein was to find a way to deal with fundamentally soul-crushing, oppressive topics in a non-soul-crushing manner, to evoke and represent how these characters’ environment drags them down, and to leave the reader with a honest sense of the significance of this, and yet to somehow avoid dragging the reader down with them to the point where they just throw the book against a wall and go outside. This is a formidable task, to say the least, and one that has claimed more than a few careers. Somehow, faced with this challenge, White Noise doesn’t just succeed – it makes success look effortless. The book portrays suffocating, exhausting, nauseating, literally borderline-schizophrenic information overload with a dry, wry, sly, somehow kind attitude that actually feels refreshing, reassuring, and even revitalizing.

There are a few ways DeLillo has of setting this atmosphere. The most overt: interspersed throughout the narrative we find strange, obtrusive interjections, total non-sequiturs with regard to what came before and what comes after, and almost always bookended by paragraph breaks. For instance…

-

Late in the evening a husband and wife are half-arguing in bed, and interspersed with the dialogue are sound bites from a nature show on TV in the next room over, the cloyingly benign narration undercutting the drama of their conversation in an all-too-familiar way.

-

Two academics walk across campus, deep in conversation, ostensibly engaged with grand ideas but also involuntarily free-associating brand names as they walk, never giving voice to these intrusive thoughts but nevertheless experiencing the private indignity.

-

A man gets into a car, with murderous intent – but before turning the key he instinctively pauses to take inventory of “trash caddies fixed to the dashboard and seat-backs, dangling plastic bags full of gum wrappers, ticket stubs, lipstick-smeared tissues, crumpled soda cans, crumpled circulars and receipts, ashtray debris … Thus familiarized, I started the engine…”

The overall effect is to create an atmosphere that’s not just devoid of drama and excitement, but one in which any drama that might crop up by chance is actively suppressed. This suffusion of useless information proves somehow fundamentally incompatible with any form of high drama.

These interjections (the frequency of which seems to positively correlate closely with the level of narrative tension, i.e. with the periods where they are most intrusive) are uniformly short. They aren’t the focus – in fact, that’s precisely their purpose: to not be focused on. They are informational entropy, background radiation, nothing more than so much noise.

In one sense, the novel serves as an exploration of just what makes the modern world so draining, an attempt to ask from whence comes its conspicuous static-ness (all senses of the word intended). The novel’s use of typical techniques in creating a thoroughly untypical narrative leads us to ask how the novel’s world differs from the worlds we’re used to finding in our fiction. The more time we spend with this question, the more the novel leads us, through implicit prompts, to a rewarding exploration of precisely the ways in which the world has changed and continues to change, and what these changes are doing to us. This might sound like hyperbole, but it’s not: This is an uncannily prescient book.

The world DeLillo depicts is one suffused by radio and television, but still pre-Internet. Even so, his characterization of its psychic qualities, of its effects on ordinary people, still ring true decades later. The ends to which we use technology, and the ways we react, psychologically, to actually having those ends satisfied, have changed far less than the technologies themselves. Heinrich would have loved Wikipedia. Babette’s obsession with call-in radio shows presages the appeal of niche interest-based social media cliques. The family’s disaster-gawking would’ve been perfectly indulged by YouTube. And the “émigré” New Yorkers’ rapid-fire and “obvious” analyses of these surreptitious interests’ underpinnings still cut deep. Technology changes, but people don’t.

Those who’ve read the book will notice I haven’t given a single word yet to its most overtly noteworthy plot point, the “airborne toxic event”. I did promise earlier to avoid major spoilers. I will say this: As wildfires rain ash down from the Seattle sky and people walk around with air-filtration masks, the idea of the Event is becoming disturbingly immediate.

This is an exceptional novel, moreso because it weighs in at only 300-odd pages and fits more into them than you’d usually find in a book twice its length. Recommended without hesitation. And, if any DeLillo fans have suggestions for what I should read next from him (this guy has written a lot of books!!), let me know.

It goes without saying that when it comes to issues of digital privacy and security, Bruce Schneier is just about the sharpest, most well-informed writer around.

For those who don’t know: In ‘94, Schneier wrote the book on cryptography (Applied Cryptography), then in ‘96 he wrote the other book on cryptography (Practical Cryptography, which literally changed my life when I read it in high school). He’s since written, blogged, and newslettered extensively, writing primarily on security issues. The dude has long since achieved luminary security guru status. It pays to pull information from as many sources as you can, but if you only care to listen to one person on security issues, that person should be Bruce Schneier.

If, like myself, you enjoy his blog but wish the posts were longer or the essays were more frequent, do yourself a favor and pick up this book. If you want to know the covert ways your privacy is being invaded every day, this is the book for you. If the topic seems too daunting to comprehend, or if you try to comfort yourself by repeating some little mantra like, “I’m not interesting enough to track, they don’t care about people like me, my obscurity secures me,” this book will change your perspective. The modern techniques of surveillance render it such a low-cost activity that this “who-wants-to-bother-watching-little-ol-me” reasoning just doesn’t work any more. It presupposes that surveillance is a personal act, and that is a false assumption. The days of targeted surveillance are numbered; these days, it turns out to be more effective to just gather all the data you can on everyone, everywhere, all the time. The game has changed, and Schneier lucidly exposes how and why.

What’s bizarre is that this whole surveillance apparatus emerged in the last few decades. It’s wholly modern, and both qualitatively and quantitatively it is wholly different from anything else in human history. This means that when it comes to this stuff, some very simple things turn out to be very hard:

-

It’s hard to level-headedly evaluate the risks, costs, and benefits that come with this apparatus. After all, we have no precedent to extrapolate from.

-

It’s hard to even know the full extent of what is taking place, because it’s so new that there are still a lot of well-kept secrets.1

-

It’s hard to regulate this space, because (again) we have no proven reference points to use when drawing up new laws, and because any existing precedent we do have is woefully underequipped to deal with the issues we currently face.2

-

It’s extremely hard, as a civilian, to stand up for yourself in “the hidden battles to collect your data and control your world” – and it’s just about impossible to withdraw from the fight completely.

-

It is, however, alarmingly easy to throw up your hands and give up, to relinquish your fundamental human right to privacy, to stop trying to protect yourself or even know what all you’d be trying to protect yourself against.

These issues and more are addressed within this book’s 400 pages, in impressively clear, authoritative, extremely information-dense fashion. It’s a whirlwind tour of where we are in the USA and worldwide with respect to issues of digital privacy and mass data collection, of how we got here, and of where we need to go if we want to transform our current society into one that respects the rights and wishes of its constituents. It includes actionable suggestions for governments, for corporations, and for individuals.

In the book’s closing acknowledgements section, Schneier explicitly thanks Edward Snowden, “whose courageous actions resulted in the global conversation we are now having about surveillance. It’s not an exaggeration to say that I would not have written this book had he not done what he did.” Data and Goliath’s premise and content both confirm Snowden’s early statement to Laura Poitras that “[NSA is] building the greatest weapon for oppression in the history of man, yet its directors exempt themselves from accountability.” This is true both in government and private industry: companies that gather and sell individuals’ data without consent are everywhere, and none of them acknowledge the impact of what they do.

I consider myself to be someone who follows these issues pretty closely, and I still learned a ton from this book. I’ve been eagerly recommending it to anyone who I think would read it. In fact, if you want, drop me a line and I’ll buy you a copy – seriously. It’s on the house.

I’m thinking of writing a longform post about this book, so I’ll try to keep this one short. Walkaway is fantastic, but you don’t have to take my word for it, because this book has just about the most impressive set of back-cover endorsements I’ve ever seen:

William Gibson: “The darker the hour, the better the moment for a rigorously imagined utopian fiction. Walkaway is now the best contemporary example I know of, its utopia glimpsed after fascinatingly extrapolated revolutionary struggle. A wonderful novel: everything we’ve come to expect from Cory Doctorow and more.”

Edward Snowden: “A dystopian future is in no way inevitable; Walkaway reminds us that the world we choose to build is the one we’ll inhabit.”

Kim Stanley Robinson: “In a world full of easy dystopias, Cory Doctorow writes the hard utopia, and what do you know, his utopia is both more thought-provoking and more fun.”

Neal Stephenson: “Cory Doctorow has authored the Bhagavad Gita of hacker/maker/burner/open source/git/gnu/wiki/99%/adjunct faculty/Anonymous/shareware/thingiverse/cypherpunk/LGTBQIA*/squatter/upcycling culture and zipped it down into a pretty damned tight techno-thriller with a lot of sex in it.”

For a book like this, it’s hard to imagine four better people to get blurbs from, and everything they say is spot-on. If anything, they’re underselling it. This is a great book, and it cannot have been easy to write. I’ve always thought that if Neal Stephenson had a more overtly political bent he’d sound a lot like Cory Doctorow (the correspondence is, of course, intended to be strongly complimentary for both parties), and this novel is strong evidence for that suspicion.

Walkaway is a novel of ideas, primarily concerned with social structures: what is possible, what is practical, and what is likely. Doctorow’s creativity is striking and he pulls no punches. This novel is optimistic and idealistic but by no means starry-eyed.

One interesting thing about the reviews quoted above is how three out of four make direct reference to this being a utopian novel. My suspicion is that this was not entirely by coincidence: if I were Cory Doctorow, I’d probably be concerned about being misinterpreted. In a sense, this novel is an exploration of ways in which utopia can emerge from dystopia, and it’s easy to imagine how people would miss the former in a world where so much of what we read is the latter.

The basic premise – skirting spoilers as much as possible – is that modern society has grown almost intolerably late-capitalist, stratified between a worker class without even a hint of upward mobility, and an upper class, the “zottas” (presumably some unimaginably large new SI prefix coined to describe the magnitude of their inflation- and greed-bloated wealth). The zottas live by a different set of rules, and from their perspective society is a kind of utopia – at least, as long as they can keep from thinking too hard about how it feels for everyone else. This seems to come easily to most of them.

Meanwhile, for the worker class, all you have is wage-slavery in a world of ultra-pervasive surveillance. Most people lead lives of quiet irrelevance, barely getting by in a world that only cares about them inasmuch as it cares about their labor. The risk-takers throw “communist parties”, breaking into unused warehouses and recommissioning abandoned manufacturing equipment, letting it spit out high-quality goods that they just give away, first-come-first-serve. Free as in beer – and the beer’s free, too.

The interesting thing about having automated fabrication of this quality is that it invalidates a core axiom of market logic: namely, that there is only so much nice stuff, and it has to get divvied up somehow, and an unfair system is better than no system at all. People in Walkaway’s “default” society still live under this assumption, but a growing number come to realize the deck is stacked against them and, well, they walk away. They just literally pack their bags and leave the city to go start a new life in the war-torn wilderness.

In walkaway, people share their fab machines gladly as long as you’re not an asshole. Feedstock for them is abundant from salvage (left over from centuries of war and climate change, one assumes). Show up with feedstock and you’re everyone’s new best friend. With the labor cost of producing something you’ve got a design for reduced to virtually nil, the idea of having long-term possessions becomes sort of quaint, and the idea of purchasing things is flat-out incoherent. Why bother?

So while the people in “default” run ever-faster on their hamster wheels, the walkaways step off, rest their legs, and take a moment to look around for the first time. The book is about what they see, and how the rest of the world reacts to what they’ve done. It gets really dark in some places, but there’s a utopian vision throughout that I found incredibly compelling. It’s a reminder that the world we choose to build is the one we will inhabit.

-

(At one point, Schneier mentions that one of the most surreal things about the Snowden leaks was how the actual facts of the NSA’s operations made even the most extreme civilian-sector conspiracy theories seem plain in contrast) ↩

-

Although in one of the later chapters Schneier does actually cite a number of potential models for future work in the form of relevant referenda and extant legislation from various governments and international bodies. This discussion alone justifies the cost of admission for anyone interested in doing policy work in this space, in my opinion. ↩