sohliloquies

Wang's Attack in Practice

29 April 2020Last time, we discussed the theory behind Wang’s attack. Now let’s cover the implementation.

The intro to Cryptopals Set 7 describes Wang’s attack as being “as difficult as anything we’ve done” in those first seven sets of problems. I would not disagree.1 That said, if we take the right approach, our implementation can end up being both concise and performant, giving us a highly readable little script that continuously generates MD4 collisions at a rate of several per minute.

We’ll be working in Python, because no one has the time to write hard code like this in less helpful languages. No, it’s not as fast as C, but it doesn’t take years off your life either.

The theory behind the attack was covered in Wang’s Attack in Theory. That post covers the “what” and “why” of Wang’s attack; this post covers the “how”.

review: MD4’s internals

Here is a full implementation of MD4 in Python.

To review, this is how we define the boolean functions F, G, H and the round

functions r1, r2, r3:

def F(x: int, y: int, z: int) -> int: return (x & y) | ((x ^ 0xFFFFFFFF) & z)

def G(x: int, y: int, z: int) -> int: return (x & y) | (x & z) | (y & z)

def H(x: int, y: int, z: int) -> int: return x ^ y ^ z

MODULUS = 1 << 32

def r1(a: int, b: int, c: int, d: int, k: int, s: int, X: Sequence[int]) -> int:

val = (a + F(b, c, d) + X[k]) % MODULUS

return leftrotate(val, s)

def r2(a: int, b: int, c: int, d: int, k: int, s: int, X: Sequence[int]) -> int:

val = (a + G(b, c, d) + X[k] + 0x5A827999) % MODULUS

return leftrotate(val, s)

def r3(a: int, b: int, c: int, d: int, k: int, s: int, X: Sequence[int]) -> int:

val = (a + H(b, c, d) + X[k] + 0x6ED9EBA1) % MODULUS

return leftrotate(val, s)

In the round functions’ arguments, X is a list of integers representing 32-bit

message words \(m_{0}, ..., m_{15}\) in order. I’m calling it X rather than

M to avoid implied associations with any fixed message value, because X’s

contents will change over the course of the message massage.

One thing that might seem odd to seasoned readers: rather than passing message

words X[k] to our round functions, we’re passing both X and k separately.

This might seem unnecessary - and strictly speaking, it is - but having a

reference to X inside the round function enables a cool trick in our round 1

massage, as you will see shortly.

Continuing our review, here is how MD4 computes all three rounds for each message block:

# round 1

a = r1(a,b,c,d, 0,3,X); d = r1(d,a,b,c, 1,7,X); c = r1(c,d,a,b, 2,11,X); b = r1(b,c,d,a, 3,19,X)

a = r1(a,b,c,d, 4,3,X); d = r1(d,a,b,c, 5,7,X); c = r1(c,d,a,b, 6,11,X); b = r1(b,c,d,a, 7,19,X)

a = r1(a,b,c,d, 8,3,X); d = r1(d,a,b,c, 9,7,X); c = r1(c,d,a,b,10,11,X); b = r1(b,c,d,a,11,19,X)

a = r1(a,b,c,d,12,3,X); d = r1(d,a,b,c,13,7,X); c = r1(c,d,a,b,14,11,X); b = r1(b,c,d,a,15,19,X)

# round 2

a = r2(a,b,c,d,0,3,X); d = r2(d,a,b,c,4,5,X); c = r2(c,d,a,b, 8,9,X); b = r2(b,c,d,a,12,13,X)

a = r2(a,b,c,d,1,3,X); d = r2(d,a,b,c,5,5,X); c = r2(c,d,a,b, 9,9,X); b = r2(b,c,d,a,13,13,X)

a = r2(a,b,c,d,2,3,X); d = r2(d,a,b,c,6,5,X); c = r2(c,d,a,b,10,9,X); b = r2(b,c,d,a,14,13,X)

a = r2(a,b,c,d,3,3,X); d = r2(d,a,b,c,7,5,X); c = r2(c,d,a,b,11,9,X); b = r2(b,c,d,a,15,13,X)

# round 3

a = r3(a,b,c,d,0,3,X); d = r3(d,a,b,c, 8,9,X); c = r3(c,d,a,b,4,11,X); b = r3(b,c,d,a,12,15,X)

a = r3(a,b,c,d,2,3,X); d = r3(d,a,b,c,10,9,X); c = r3(c,d,a,b,6,11,X); b = r3(b,c,d,a,14,15,X)

a = r3(a,b,c,d,1,3,X); d = r3(d,a,b,c, 9,9,X); c = r3(c,d,a,b,5,11,X); b = r3(b,c,d,a,13,15,X)

a = r3(a,b,c,d,3,3,X); d = r3(d,a,b,c,11,9,X); c = r3(c,d,a,b,7,11,X); b = r3(b,c,d,a,15,15,X)

This may look pretty arbitrary. That’s fine; I won’t try to convince you that it

isn’t. I included this code because it shows the values of k and s used at

each intermediate state. We’ll need these values for our massage.

defining constraints

The core of Wang’s attack is a list of constraints on MD4’s intermediate states. Nearly all of these constraints fall into one of three types: zero constraints, one constraints, and equality constraints. This taxonomy suffices for all the constraints we will be implementing.

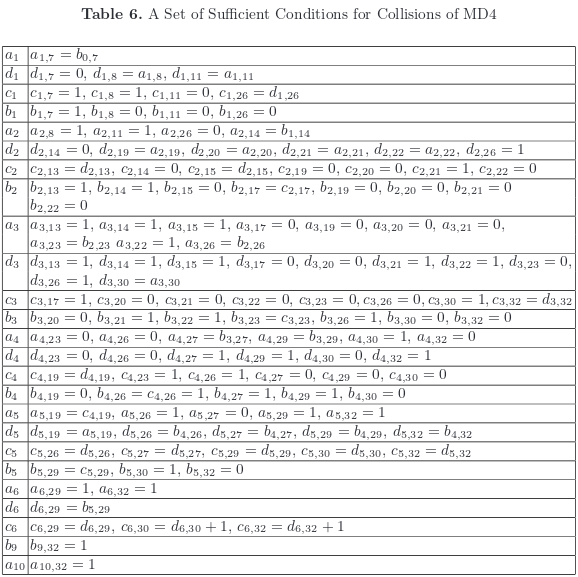

For reference, here is the list of constraints:

Since these constraints are the core of the attack, let’s make them the core of our program as well - or at least its starting point.

As a rough draft, we could represent zero constraints with a class like this:

class ZeroConstraint:

def __init__(self, ind: int):

self.ind = ind

def check(self, word: int):

return word & (1 << self.ind) == 0

def massage(self, word: int):

mask = (1 << self.ind) ^ 0xFFFFFFFF

return word & mask

This is simple enough, and you can write similar classes for each other type of constraint.

Already, though, some potential improvements present themselves. For instance,

we can improve the check() and massage() methods’ performance by

precomputing the masks they use like so:

class ZeroConstraint:

def __init__(self, ind: int):

self.ind = ind

self.mask = 1 << ind

self.mask_inv = self.mask ^ 0xFFFFFFFF

def check(self, word: int):

return word & self.mask == 0

def massage(self, word: int):

return word & self.mask_inv

Another idea: when a state is subject to multiple constraints of the same type

(e.g. zero constraints on several indices), we might as well enforce those

constraints simultaneously. Let’s implement this by making __init__ accept a

variable number of indices, not just one.

We’ll want our other constraint types to support that same pattern, so while we’re at it let’s pull that logic out into a superclass and subclass it.

class Constraint:

def __init__(self, *inds):

self.inds = inds

self.mask = 0

for ind in inds:

self.mask |= (1 << ind)

self.mask_inv = self.mask ^ 0xFFFFFFFF

class Zeros(Constraint):

def check(self, word_1: int, word_2=None):

return word_1 & self.mask == 0

def massage(self, word_1: int, word_2=None):

return word_1 & self.mask_inv

class Ones(Constraint):

def check(self, word_1: int, word_2=None):

return word_1 & self.mask == self.mask

def massage(self, word_1, word_2=None):

return word_1 | self.mask

class Eqs(Constraint):

def check(self, word_1, word_2):

return (word_1 & self.mask) == (word_2 & self.mask)

def massage(self, word_1, word_2):

return (word_1 & self.mask_inv) | (word_2 & self.mask)

The above methods rely on two properties: word & mask sets bits in word to 0

wherever the corresponding bits in mask are 0, and word | mask sets bits in

word to 1 wherever mask is 1. If any of the above code seems esoteric, this

might be a good time to brush up on the basics

of bitwise operations.

You’ll notice that Eqs.check() and Eqs.massage() both take two arguments.

This is because the corresponding constraints all involve pairs of states. In

Eqs.massage(), the first state is the one that gets massaged; the constrained

bits are first zeroed, then set to equality with the second state.

I’ve added optional, unused extra arguments to the check() and massage()

methods for Zeros and Ones as well, to keep the method signatures

consistent. This might look a little silly, and it’s not strictly necessary, but

it allows us to massage constraints of all three types in the same loop without

having to keep track of which constraint type we’re dealing with on any given

iteration.

Now that we’ve defined these classes, let’s express the attack’s round-one constraints in terms of them:

round_1 = [[Eqs(6)],

[Zeros(6), Eqs(7, 10)],

[Zeros(10), Ones(6, 7), Eqs(25)],

[Zeros(7, 10, 25), Ones(6)],

[Zeros(25), Ones(7, 10), Eqs(13)],

[Zeros(13), Ones(25), Eqs(18, 19, 20, 21)],

[Zeros(13, 18, 19, 21), Ones(20), Eqs(12, 14)],

[Zeros(14, 18, 19, 20, 21), Ones(12, 13), Eqs(16)],

[Zeros(16, 18, 19, 20), Ones(12, 13, 14, 21), Eqs(22, 25)],

[Zeros(16, 19, 22), Ones(12, 13, 14, 20, 21, 25), Eqs(29)],

[Zeros(19, 20, 21, 22, 25), Ones(16, 29), Eqs(31)],

[Zeros(19, 29, 31), Ones(20, 21, 25)],

[Zeros(22, 25, 31), Ones(29), Eqs(26, 28)],

[Zeros(22, 25, 29), Ones(26, 28, 31)],

[Zeros(26, 28, 29), Ones(22, 25), Eqs(18)],

[Zeros(18, 29), Ones(25, 26, 28)]]

This lists out the constraints on each round-one state, one row per state, starting with \(a_{1,7} = b_{0,7}\) and ending with \(b_{4,19} = b_{4,30} = 0\) and \(b_{4,26} = b_{4,27} = b_{4,29} = 1\).

We are 0-indexing our bit indices in all of these constraints, in direct defiance of the paper’s 1-indexed notation. This makes for a bit of a hassle when transcribing indices from the paper to our code, but it makes our code itself much cleaner.2

Note that none of these Eqs constraints specify which two states they apply

to; there’s no need for them to, since all of them apply to a state and its

immediate prior (e.g., in the case of the first row, the constraint is between

\(a_1\) and \(b_0\), and for the second row the constraints involve \(d_1\) and

\(a_1\)).

This list has 94 constraints. A round-one massage which enforces each constraint

individually would have to make 94 calls to massage(); by consolidating

constraints, we’ve reduced this to 41 Constraint instances and thus 41 calls

to massage(). This optimization alone yields a performance improvement of 2.3x

over a naïve implementation.

massaging constraints: round one

Let’s write a function to take an input message (as bytes) and massage it.

First, we’ll need to break the message up into a list of ints sized to 32 bits

apiece. struct.unpack is the tool of choice for this type of byte conversion.

We’ll also want to initialize our state variables and keep a log of all intermediate states.

def massage(message, quiet=True):

X = [struct.unpack("<I", word)[0] for word in bytes_to_chunks(message, 4)]

a, b, c, d = 0x67452301, 0xEFCDAB89, 0x98BADCFE, 0x10325476

state_log = [a, d, c, b]

(note: this makes use of a helper function, bytes_to_chunks, which is defined here)

Recall that massaging first-round constraints is a two-step process: first, we

modify the state variable’s value so that our constraints are satisfied; second,

we modify the corresponding message word to ensure that r1 returns the desired

new value for our state variable.

Since the message is stored in a mutable array, we can wrap our round function with a helper which derives and performs the necessary message modifications in place:

def f(a, b, c, d, k, s, X):

# serves as normal round function, but also adjusts X as it goes

a_new = r1(a, b, c, d, k, s, X)

for suite in round_1[k]:

a_new = suite.massage(a_new, b)

X[k] = (rrot(a_new, s) - a - F(b, c, d)) % MODULUS

state_log.append(a_new)

return a_new

The math behind the derivation of X[k]’s value was covered in my previous post on Wang’s attack.

Note that this function takes advantage of the fact that all three constraints’

massage() methods accept two arguments, even if only one argument is needed.

This was alluded to earlier, when we were defining our constraint classes. This

allows us to avoid having to determine constraint suites’ method signatures

through isinstance checks, which is good for performance.

Now that we have this function, we can apply a full round-one message massage by

simply copying the round-one MD4 code block from above and swapping out r1 for

f:

a = f(a,b,c,d,0x0,3,X); d = f(d,a,b,c,0x1,7,X); c = f(c,d,a,b,0x2,11,X); b = f(b,c,d,a,0x3,19,X)

a = f(a,b,c,d,0x4,3,X); d = f(d,a,b,c,0x5,7,X); c = f(c,d,a,b,0x6,11,X); b = f(b,c,d,a,0x7,19,X)

a = f(a,b,c,d,0x8,3,X); d = f(d,a,b,c,0x9,7,X); c = f(c,d,a,b,0xA,11,X); b = f(b,c,d,a,0xB,19,X)

a = f(a,b,c,d,0xC,3,X); d = f(d,a,b,c,0xD,7,X); c = f(c,d,a,b,0xE,11,X); b = f(b,c,d,a,0xF,19,X)

Since f modifies the message word list X in place, we just have to execute

this block; by the end of it, our round-one massage will be complete.

Once we’re satisfied with our massage, we can pack the message back up into bytes and return it:

return b''.join(struct.pack("<I", word) for word in X)

That’s right - for round one, that really is all it takes.

applying the message differential

We just wrote a massage function which takes an arbitrary length-64 bytestring

and turns it into a promising candidate message M. Before we can check whether

M is part of a collision, we have to be able to compute M', aka M + D.

The differential modifies three message words. We can encode these words’ indices and their internal differentials like so:

DIFFERENTIALS = ((1, 1 << 31),

(2, (1 << 31) - (1 << 28)),

(12, -(1 << 16)))

Then applying the differential is straightforward:

def apply_differential(m):

words = bytes_to_chunks(m, 4)

for i, delta in DIFFERENTIALS:

m_i = (struct.unpack("<I", words[i])[0] + delta) % MODULUS

words[i] = struct.pack("<I", m_i)

m_prime = b''.join(words)

return m_prime

You might be wondering why DIFFERENTIALS is a nested tuple, not a dictionary.

Granted, it would be natural to define it as {1: 1 << 32, ...}, and that

definition would read quite well, its usage would not. We don’t want to look

indices up in this data structure; we just want to loop over its pairs of

values. By storing the differential as pairs of values, we avoid having to call

.items() on it. That has benefits for both performance and clarity.

finding collisions

Now that we know how to derive M' from M, the next step is to generate M

values in a loop, checking each one to see whether M and M' collide. We can

encapsulate this search in a generator function like so:

def find_collisions():

for i in itertools.count():

# occasionally print something so the user knows we're still running

if i & 0xFFFF == 0:

print(end=".", flush=True)

# massage some random bytes. if we get a collision then yield (m1, m2)

orig = random.getrandbits(512).to_bytes(64, 'big')

m1 = massage(orig)

m2 = apply_differential(m1)

if md4(m1) == md4(m2):

yield m1, m2 # we've got a hit!

After trying a bunch of other options, I’m pretty sure that

random.getrandbits(512).to_bytes(64, 'big') is the fastest way to get a

64-byte3 pseudorandom4 bytestring in Python.

You can speed up find_collisions() by using a crypto library’s binding for

md4 (e.g. pycrypto’s Crypto.Hash.MD4). This will likely run much faster

than any Python-native implementation, which is important since our hot loop

runs md4 at least twice per iteration.

There’s another potential speedup that I’ve skipped implementing here because I feel like the code reads better without it. If you’re curious, though, I’ve sketched the idea out in the following footnote.5

Once we have this function, we can just loop over it and print what it yields.

if __name__ == "__main__":

print("Searching for collisions...")

print(datetime.now())

print()

for m1, m2 in find_collisions(report_trial_rate=True):

print()

print(datetime.now())

print("Collision found!!")

print(f"md4(bytes.fromhex('{m1.hex()}')) == {md4(m1)}")

print(f"md4(bytes.fromhex('{m2.hex()}')) == {md4(m2)}")

print()

Using this algorithm for a full round-1 massage, I measured a per-trial success probability of appx \(2^{-25}\). With just these constraints my implementation was finding about one collision per day. At that rate the attack is actually practical, making this a good time to test your attack code.

massaging constraints: round two

Let’s talk about how to get from one collision per day to several per minute.

This part of the massage will end up being somewhat less terse than round one. Two reasons: the constraints are more varied, and we have to start cleaning up side effects.

Let’s write a helper function for cleaning up side effects. This will find the

message word that produces a given round-1 state. It works by inverting r1.

We’ll give it the index of the message word, the leftrotate shift amount for

the given step, and our state log (passed in as s to keep our one-liner

narrow).

# returns a message value tailored to produce the expected intermediate state

def r1_inv(k, rot, s):

return (rrot(s[k+4], rot) - s[k] - F(s[k+3], s[k+2], s[k+1])) % MODULUS

When we make changes to any message word, we can prevent those changes from spreading through round one by using this function to update the following message words.

Let’s also define a round_two constraint list analogous to round_one. This

is only a partial list of constraints, and it is not meant to be consumed

automatically. It’s still useful though, because it lets us define and

initialize these constraint objects once, when the program first starts, rather

than (say) creating them over and over inside massage.

round_2 = [[Zeros(26), Ones(25, 28, 31), Eqs(18)],

[Eqs(18), Eqs(25, 26, 28, 31)], # d_5 has equality constraints for both a_5 & b_4

[Eqs(25, 26, 28, 29, 31)],

[Zeros(31), Ones(29), Eqs(28)],

[Ones(28)]]

Now, here’s how we massage some specific states.

\(a_5\)

\(a_5\) is the first state in round two.

We’ll start by computing a preliminary value for \(a_5\), then we’ll massage it

and modify X[0] to produce the massaged state.

This change to X[0] will produce side effects back in round one. As described

in the last post, we’re going to end up changing words 0 through 4 of the

message in order to contain those side effects and avoid perturbing our

round-one states any more than is absolutely necessary.

Here’s the full massage step for \(a_5\):

######## a5

a_4 = a

a = r2(a,b,c,d,0,3,X)

for suite in round_2[0]:

a = suite.massage(a, c)

X[0] = (rrot(a, 3) - a_4 - G(b, c, d) - ROUND_2_CONST) % MODULUS

state_log[4] = r1(state_log[0], state_log[3], state_log[2], state_log[1], 0, 3, X) # adjust a_1

X[1] = r1_inv(1, 7);

X[2] = r1_inv(2, 11);

X[3] = r1_inv(3, 19);

X[4] = r1_inv(4, 3)

As noted in the last post, our constraints on \(a_1\) and \(a_5\) tend not to conflict with each other. As a result, we can just compute a new value for \(a_1\) and hold the next four intermediate states constant.

\(d_5\)

You’ll recall that our methodology for massaging \(d_5\) was somewhat more involved. The idea is to enforce all our constraints on \(m_4\) directly. See Wang’s Attack in Theory for an explanation of how this works.

Here is an implementation of this massage methodology:

######## d5

N_1 = (state_log[4] + F(state_log[7], state_log[6], state_log[5])) % MODULUS

N_2 = (d + G(a, b, c) + ROUND_2_CONST) % MODULUS

m_4 = 0

b_rot = rrot(b, 5)

def set_d5_bit(N_orig, m, ind, x):

N = (N_orig + m) % MODULUS

return (N & (1 << ind)) ^ x

m_4 |= set_d5_bit(N_1, m_4, 4, 1 << 4)

m_4 |= set_d5_bit(N_1, m_4, 7, 1 << 7)

m_4 |= set_d5_bit(N_1, m_4, 10, (state_log[7] >> 3) & (1 << 10))

m_4 |= set_d5_bit(N_2, m_4, 13, (a >> 5) & (1 << 13))

m_4 |= set_d5_bit(N_2, m_4, 20, b_rot & (1 << 20))

m_4 |= set_d5_bit(N_2, m_4, 21, b_rot & (1 << 21))

m_4 |= set_d5_bit(N_1, m_4, 22, 0)

m_4 |= set_d5_bit(N_2, m_4, 23, b_rot & (1 << 23))

m_4 |= set_d5_bit(N_2, m_4, 24, b_rot & (1 << 24))

m_4 |= set_d5_bit(N_2, m_4, 26, b_rot & (1 << 26))

X[4] = m_4

d = r2(d, a, b, c, 4, 5, X)

# re-massage a_2 and make sure d_2's equality constraints with a2 still hold

state_log[8] = r1(state_log[4], state_log[7], state_log[6], state_log[5], 4, 3, X)

state_log[9] = round_1[5][2].massage(state_log[9], state_log[8])

# contain the effects of these changes to a_2 and d_2

X[5] = (rrot(state_log[9], 7) - state_log[5] - F(state_log[8], state_log[7], state_log[6])) % MODULUS

X[6] = r1_inv(6, 11)

X[7] = r1_inv(7, 19)

X[8] = r1_inv(8, 3)

X[9] = r1_inv(9, 7)

This step is a little strange in that it initializes \(m_4\) to 0 and then sets only the required bits; as a result, any unconstrained bits will default to 0.

A particularly pedantic critic might point out that this limits us to sampling collisions from a proper subset of the full collision space.6 This is true - but it’s a big subset, with more collisions than we’ll ever need, so I’m not too concerned. Plus, I think the code reads better this way, and it runs marginally faster. It would be interesting to measure whether it influences the success probability by introducing any biases in later states.

\(a_6\)

We’re just going to skip over \(c_5\) and \(b_5\), as they are not easy to work with.

\(a_6\) is another state whose constraints can sometimes interfere with our round-one constraints. The failure rate is low but nonzero. My (somewhat lazy) solution is to just regenerate the block from scratch whenever a failure is detected.

I’ve experimentally determined that the round 2 massage has a better chance of leaving us with both sets of conditions satisfied than the round-one massage does, so we’ll use the round 2 massage. My code to massage \(a_6\) looks like this:

######## c5 and b5 (just skip over these two)

c = r2(c,d,a,b,8,9,X)

b = r2(b,c,d,a,12,13,X)

######## a6

a_5 = a

a = r2(a,b,c,d,1,3,X)

a = round_2[4][0].massage(a, b)

X[1] = (rrot(a, 3) - a_5 - G(b, c, d) - ROUND_2_CONST) % MODULUS

state_log[5] = r1(state_log[1], state_log[4], state_log[3], state_log[2], 1, 7, X)

# could probably get rid of this while loop w/ enough careful analysis

while (not round_1[1][0].check(state_log[5], None)

or not round_1[1][1].check(state_log[5], state_log[4])

or not round_1[2][2].check(state_log[6], state_log[5])):

X[1] = random.getrandbits(32)

a = r2(a_5,b,c,d,1,3,X)

a = round_2[4][0].massage(a, b)

X[1] = (rrot(a, 3) - a_5 - G(b,c,d) - ROUND_2_CONST) % MODULUS

state_log[5] = r1(state_log[1], state_log[4], state_log[3], state_log[2], 1, 7, X)

X[2] = r1_inv(2, 11)

X[3] = r1_inv(3, 19)

X[4] = r1_inv(4, 3)

X[5] = r1_inv(5, 7)

I’d say this is probably the least elegant part of my implementation – but it works.

The while loop is only entered about 0.75% of the time, or about once every

133 trials. When entered, it exits after about 17 iterations on average.

I suspect it would be possible to improve this by applying a similar method as

with \(a_6\). If successful, this would let us drop the constraint checks and

the while loop, which would improve the script’s overall hash rate. Maybe

someday I’ll try that. Or maybe you will :-)

Anyway, this much of a massage is enough to produce a few collisions per minute. Past this point, side effects get really hard to manage, so we’ll stop here.

conclusion

If your implementation works, you should be able to discover collisions pretty quickly. If you have a practical need for MD4 collisions, I’m not going to ask what you do for a living but I am going to suggest you look at some later research on the subject, e.g. Yu Sasaki et al., 2007 (PDF link).

Later attacks identified new MD4 message differentials and new sets of sufficient conditions, but the basic concepts behind how to implement the attack are relatively invariant. The core ideas in this blog post should transfer well to more recent differential attacks on MD4 and related functions.

If you’d like to see what this attack looks like in practice, my take on it can be found here.

I’m measuring a success probability of about \(2^{-17.3}\) using the techniques described in this post. Running in a Qubes VM on an old ThinkPad T420s, I’m measuring ~8000 trials per second and an average success rate of just over three collisions per minute.

And frankly, after how much work this attack took, three collisions per minute is plenty for me.

-

Although an honorable mention goes to challenge 48, which covers Bleichenbacher’s attack on RSA with PKCS 1.5. I’d rate Wang’s attack as more difficult overall, but the two attacks do require comparably psychotic levels of attention to detail. ↩

-

The alternatives would be to either: (1) Use 1-indexed notation throughout our entire script (no thank you), or (2) mix the two conventions, use some naming system that distinguishes between constants that come from the paper and constants that come from anywhere else, and treat constants as 0-indexed or 1-indexed based on their origin (again, no thank you). ↩

-

Or any other length, not just 64 bytes, naturally. For n bytes, precompute

8*nand userandom.getrandbits(8*n).to_bytes(n, 'big'). My performance tests did not indicate any significant difference between using ‘big’ or ‘little’ here, but YMMV. ↩ -

Not cryptographically secure randomness - but in this case it doesn’t have to be! ↩

-

Here’s the idea: Currently, within

find_collisions, bothmassageandapply_differentialtake a message as a bytestring, break it into chunks, callstruct.unpackon the chunks, manipulate them, thenstruct.packthe result. An alternative implementation could simply generate our input message as a list of ints, rewritemassageandapply_differentialto operate on that list directly, and onlypackit back to a bytestring when we’re ready to try a collision. This would likely run a little faster; personally, though, I think it might be harder to read. But hey - maybe this can be how you write a version of the attack that outperforms mine :-) ↩ -

The alternative would be to initialize m_4 to

random.getrandbits(32), zero all the bits we’ve got constraints on, then proceed as above. That’s not too difficult, but I just don’t feel like it’s really necessary either, and – as I keep finding myself saying – the code is simpler this way. ↩